Apr 30–Jun 30, 2025

Online

-

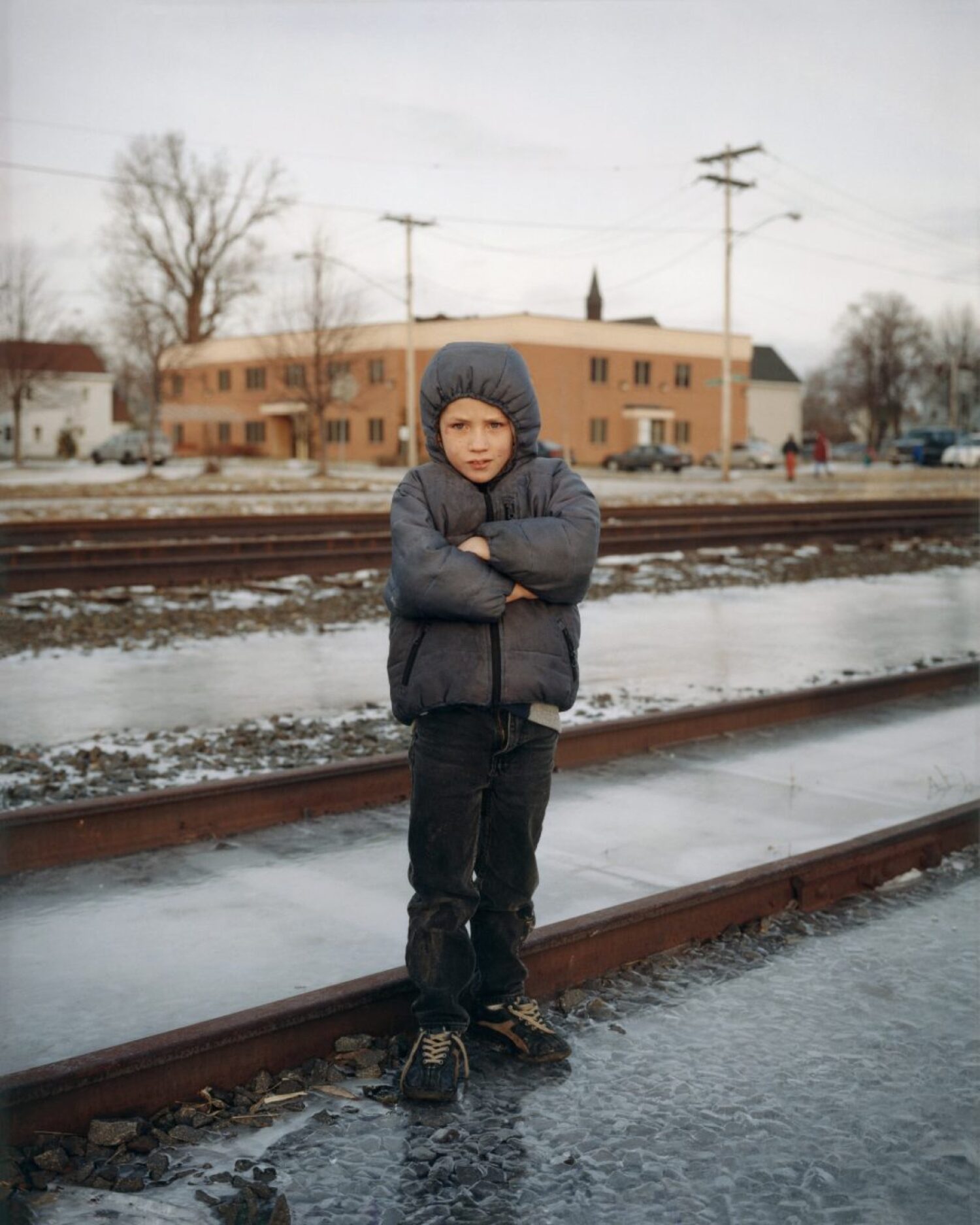

1/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

2/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

3/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

4/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

5/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

6/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

7/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

8/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

9/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

10/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

11/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

-

12/12: Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from King, Queen, Knave. Courtesy of the artist

Gregory Halpern is an American photographer and the author of eight monographs. His photographs are held in the collections of several major museums, including The Museum of Modern Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, and the Fotomuseum Antwerpen. He lives in Rochester, New York, with his wife, Ahndraya Parlato, and their two daughters. He is a professor of photography at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Silver Eye Scholar and senior Jean Ortiz recently spoke with the artist about his decades-long portrayal of his hometown of Buffalo, New York, including for his latest monograph King, Queen, Knave. Below are edited highlights from their recent conversation.

Jean Ortiz: So I guess quickly, for people who might not know you, tell me a little bit about your background and how your practice developed. How did you get into photography?

Gregory Halpern: Yeah, I always liked looking at photographs as a kid, just how they were made and constructed. I guess in terms of composition and light, I saw a couple of books when I was a kid. I saw this Paul Strand book, and those were the first "art photographs" I saw. One of the things that struck me was that there were these beautifully composed pictures, but often of everyday people. And I thought it was interesting that there was this really nuanced and beautiful way of looking at these everyday people. And then I saw a book by Milton Rogovin in Buffalo. I've talked about that one a lot. It's called Triptychs, an amazing book in which he visited people over the course of twenty years and would photograph them, usually three times over time. That book really moved me, and I think it was that moment when I was probably twelve or thirteen years old when I thought I wanted to make pictures, specifically pictures of people. Yeah, but I didn't actually go to school for it until much later, until graduate school.

JO: Yeah, I tried to go through your CV and noticed that you studied history for your bachelors if I'm correct?

GH: Right, history and literature, both. So I had some catching up to do. I think when I went to graduate school, I didn't know that much about photography, but the history of literature, I mean literature in particular, was pretty helpful for me. Just thinking about the structure of how you tell stories and thinking about that space between fiction and non-fiction, so in a way it was really helpful and inspiring. You know, even though I got sort of a slower start.

JO: Was there any influence in history per se? I remember, in one of your panels, you started referring to the history of Buffalo specifically. I believe you talked about Bethlehem Steel. You were fascinated with that landscape, so how does history inform your photographs?

GH: Yeah, that's a question. I was really fascinated by the history of Buffalo as a post-industrial city, and I'm sure you can feel that in Pittsburgh; although I think Pittsburgh has reinvented itself a little bit, but Buffalo's population has grown for the first time in 50 years in the last couple of years. Basically, we've been getting tons of immigrants and refugees, which has been an amazing thing for the city, you know, because they've really brought a lot of life to the city despite often fleeing from really tough situations, but anyway, that's in the history. The city’s population has been shrinking forever, and until that happened, you just feel it. You feel it in the landscape, sort of like dinosaurs almost, if you see them around the city. You know, former steel mills and whatnot, and what it's like to be a kid and see them. I don't know; it's compelling and strange and spooky. My brother and I used to explore these sites, and they're sort of legendary in the city’s history. Once, the site of the world's biggest steel mill was in Buffalo. The city is both sort of proud of its past and also sort of mourns its past, so it definitely plays a role somehow. …

Yeah, and like anything in a way, anything made, any work of art made in Buffalo in some way I think is really influenced by that history and those economics for better or worse, and so to me it's like you can't totally contextualize the images. They're not necessarily about deindustrialization, but I think they're very much informed by it.

JO: So my next question would be, what was the process for starting King, Queen, and Knave, and what personal feelings that you have going into the project? What motivated you to really start digging into your hometown?

GH: It started weirdly when I was living in California. When I went to graduate school out in San Francisco. It was really, I discovered Los Angeles as a place or an idea because of ZZYZX, have you seen that book?

Yeah, I hadn’t yet figured out that idea of making ZZYZX, and so I was really kind of lost in a way and you have to come up with a project in grad school, a significant project, and it kind of dawned on me that if there was something that I really cared about. Like if there was one thing I was going to be able to do, I knew a place that I thought I could make good work in a relatively short period of time. I had one semester when I was gonna go back home to Buffalo, and it was winter. It was a winter break between semesters, so I had about a month at home, and I just photographed every day for a month and really sort of embraced the feeling and the look of winter. And this would've been like 2003 or something.

So there are a few pictures in the book that are actually from that project, which was my thesis project, and ever since that project, I live like an hour away, I have kind of always just gone back with my camera to visit my friends or family. It's like chipping away at it. You know, it was never that kind of thing, the way with LA. I moved there for a year. It was never like that. It was just a thing that I was doing in the background over a long period of time.

JO: And it's interesting to me how you kept going to Buffalo, I guess other photographers are more outwardly trying to find what they care about outside of their hometown, but you seem to have gone inward and resonate with the place you grew up the most.

GH: Yeah, I mean what happened was I did this project about Guadeloupe, an island in the French Caribbean. It was a commission from the Hermes Foundation to do something in France, and I chose to do it in Guadeloupe and the French Caribbean. You know, while I was there, I felt more distant from the people I was photographing than I probably ever had before because I was just an outsider in so many ways but especially because I'm speaking terrible French. I'm White, most of the people on the island are Black, and it's just a different history and culture and I really struggled with the project. I felt like after that, the next thing I wanted to do is to go home to make this project that felt like it was more in my backyard. So, in a way, it was a reaction to that time in Guadeloupe. I thought, OK, it's time to actually focus on this Buffalo project, and it turned into a book, and so I spent another, I guess maybe three or four years sort of just trying to finish that Buffalo project, and in a way, it came out of that desire to go home.

JO: King Queen Knave has such a nice narrative structure. I've gone through like every picture and tried to pull words to it in a way. And I think the more interesting part to me is towards the end when it becomes almost like a resurrection, but speaking about life and death in a way. I'm not sure if I'm getting that correct but those were the feelings that were coming up for me. So does there seem to be themes of life, death, and ascendance?

GH: Yeah, definitely. Yes, I was thinking about the life cycle of Buffalo as a city and then the life cycle that you can see in the seasons. Yeah, just thinking about life and death a lot and how to image that, and then towards the end, there is this, well, death, I think, has been associated with that sort of downward movement of like gravitational pull, entropy, and falling right, so there's this kind of upward movement that happens towards the end that I think of is sort of pushing back against, and giving a sense of possibility. I don't really know if I could or want to pin down what that means, but I think floating or ascension makes sense to me as words that could be associated with it.

JO: So when you create kind of worlds by photographing place, like with ZZYZX and King, Queen, Knave, you've created these worlds that you've tailored for us in some sense, but also kind of documenting. What does it mean to you? To completely photograph a place and immerse yourself in it?

GH: I guess it's like for me, it's just a slow process of spending time in a place and getting to know the feeling. Maybe it's more just getting to find pictures that somehow convey what the place actually feels like to you, and that actually do that for a viewer, and that for me, it just takes a lot of time looking and walking, and exploring, and you know, returning to a place in a different light and making a lot of mistakes. Yeah, but it's a really enjoyable process. It's like it's hard to feel present in the world these days because it's so easy to be distracted but when I'm out photographing, it's a really enjoyable process of just like interacting with a place and whatever it sends your way you know, be it a thing or a person. Yeah there's just a lot of time doing that, trying to be open to see what it sends your way.

Participating Artist

Gregory Halpern is an American photographer and the author of eight monographs. His photographs are held in the collections of several major museums, including The Museum of Modern Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, and the Fotomuseum Antwerpen. His work has been featured in group exhibitions at the International Center of Photography, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, the George Eastman Museum, the Cincinnati Art Museum, the Fotomuseum Antwerpen, and Pace/MacGill in New York. He is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, a member of Magnum Photos and is represented by Loock Gallery in Berlin and Huxley-Parlour in London. He holds a BA in History and Literature from Harvard University and an MFA from California College of the Arts. He lives in Rochester, New York with his wife, Ahndraya Parlato, and their two daughters. He is a professor of photography at the Rochester Institute of Technology.