Mar 30–Apr 30, 2021

Online

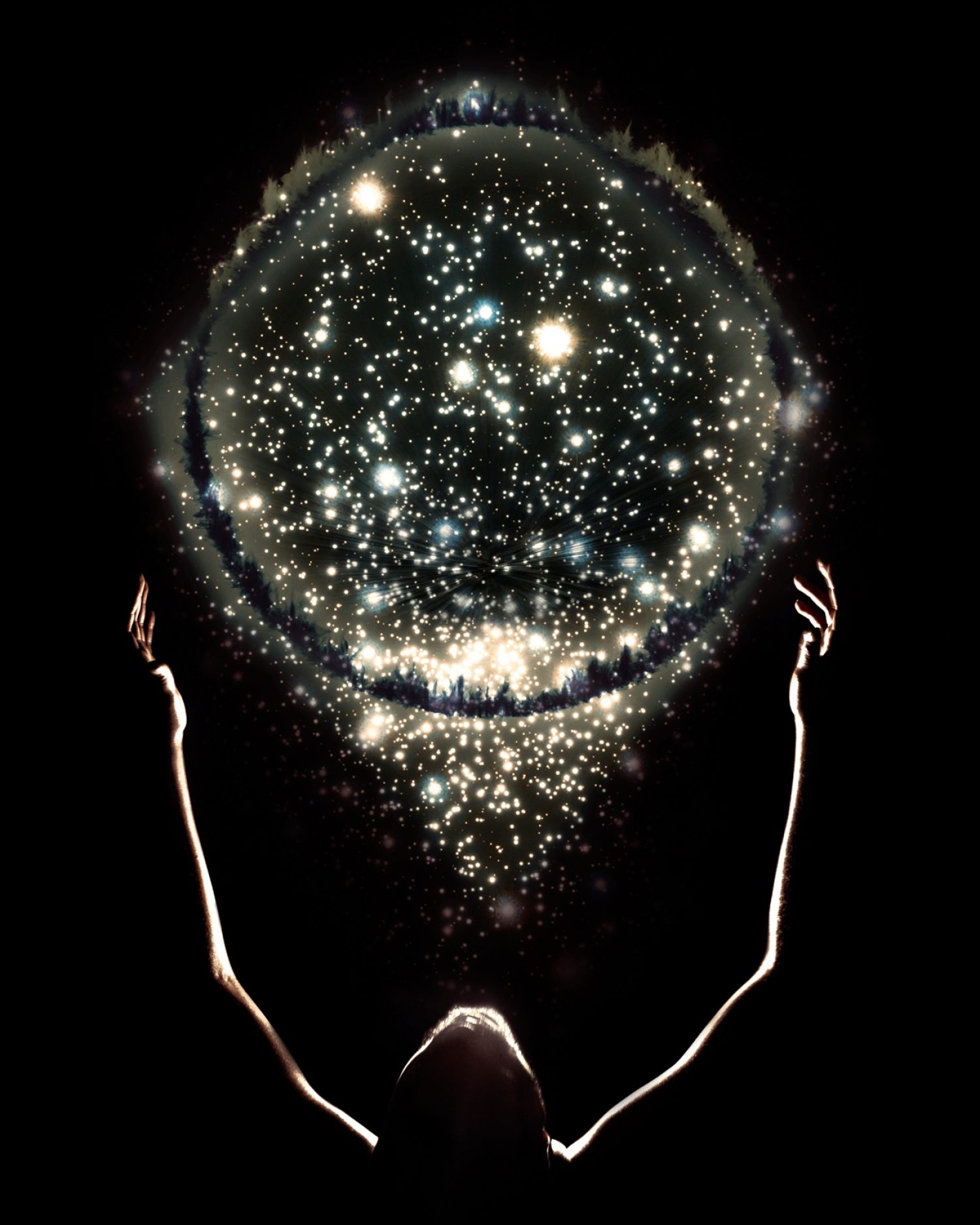

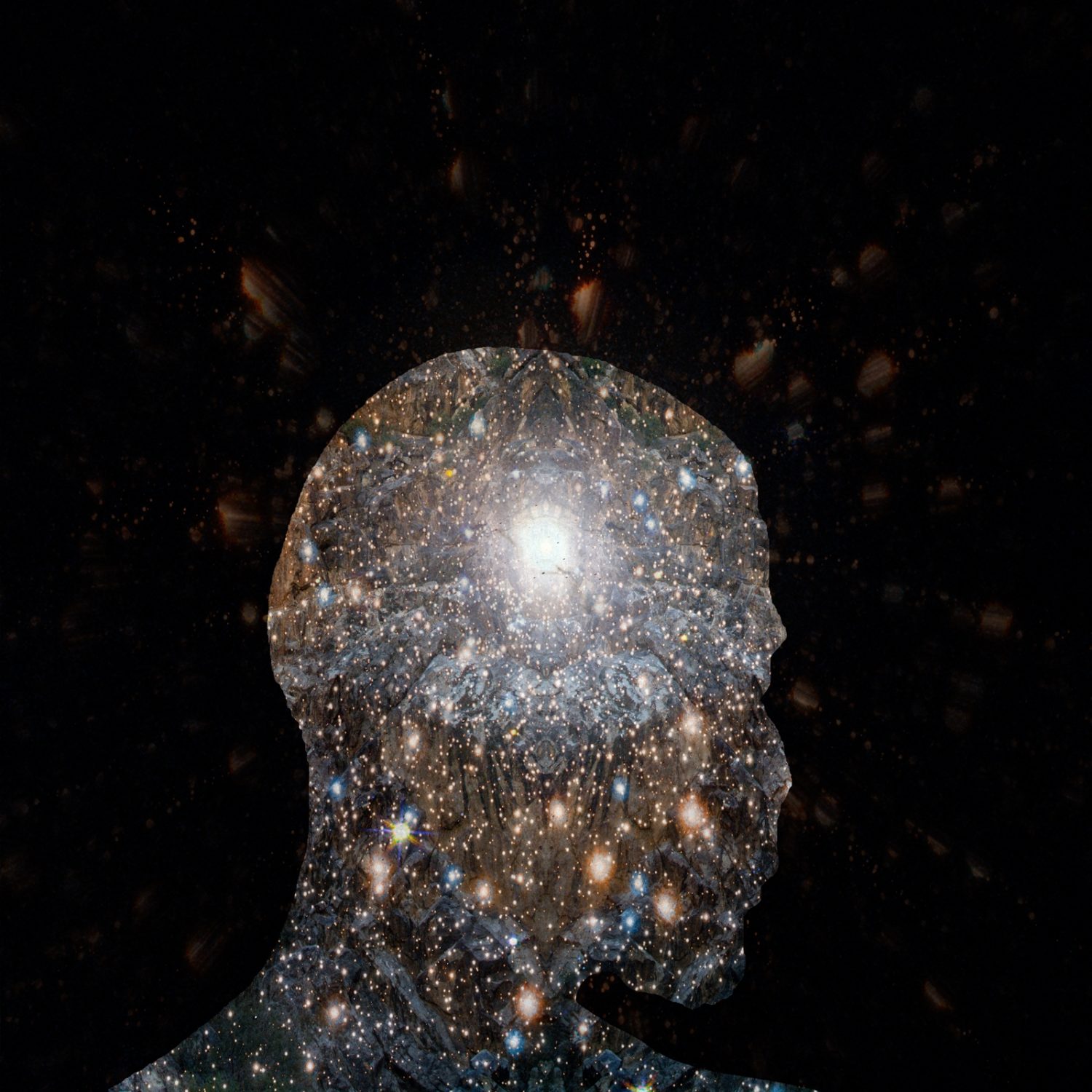

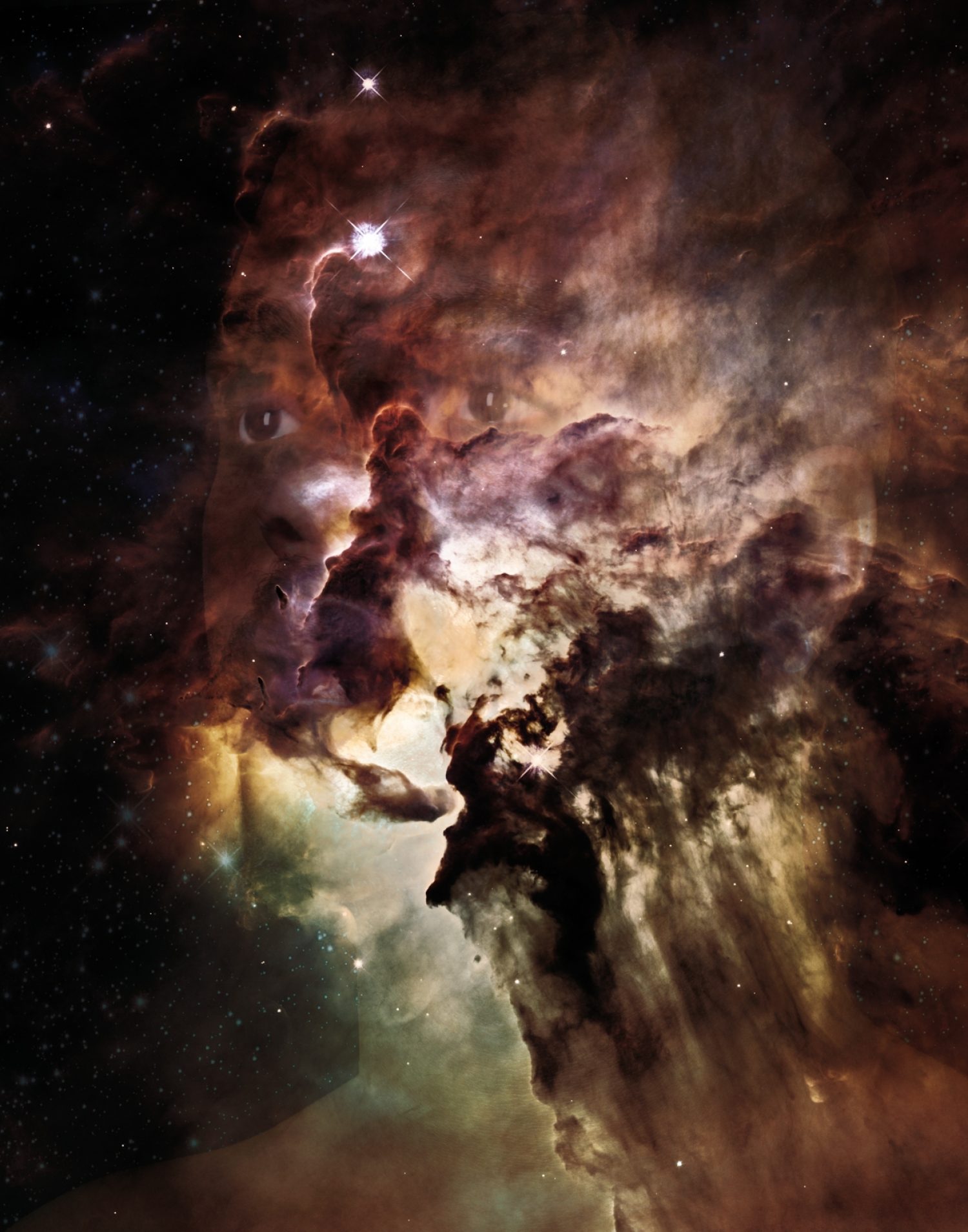

Granville Carroll is a visual artist based in Rochester, New York. Carroll is an Afrofuturist, with his work reflecting this by examining a cross-section of the real and spiritual world, while also looking inwards on his own identity. Images are manipulated and restructured to reflect these themes, and to ask us what it means to be human at the very root of existence. In his thesis work Because the Sun Hath Looked Upon Me, Carroll reaches a crossing of spirituality, philosophy, and the cosmos. This project explores the physical, natural world in a manner that leads to a deeper understanding of what it means to be black, while at the same time suggesting that when confronted with social stigma based on race humanity is more than their physical being. The photographic project is named after a quote in Chapter 1, Verse 6 of the biblical book Song of Solomon that encompasses all of Granville Carroll's themes within his images; "Look not upon me, because I am black, because the sun hath looked upon me.”

Jacob Sizemore is a senior at Point Park University studying Photography and a Silver Eye Scholar.

Jacob Sizemore: In your body of work Because the Sun Hath Looked Upon Me you deal with spirituality, directly referencing Song of Solomon in the title of the work, how did you connect your personal journey of spirituality with black identity in these photographs?

Granville Carroll: When I started Because the Sun Hath Looked Upon Me I was trying to find a balance between how you talk about something very personal and something on a larger scale. Looking at growing up as a black American, Christianity is very much a part of that community in a lot of ways. In the history of Africans who were sent over to America, they were stripped of their spiritual identities and then converted to Christianity. I wanted to dive deeper beyond that to see what is actually the spiritual path beyond the oppressor. Personally, growing up in the church I’ve always asked questions about religion and what it’s supposed to be about, and then finding a connection within nature to try and piece all those things together. Because the Sun Hath Looked Upon Me was sort of this investigation into my own personal history, but then also how that extends into the African diaspora and the history of the whole community.

JS: This body of work makes use of digital technologies for the compositing of images, how was this methodology that mixes the physical and digital used as a way to reimagine physical space?

GC: My process is really important to the concepts I work with, so being able to take an image and then bring it into a software allows me to act as a co-creator. I’m taking the indexical, physical parts of the world, but then I’m reworking them to create these new imaginative spaces or identities. The process becomes really important in that sense, and as I’m working a lot of times I don’t actually plan exactly what an image is going to look like. I might have an idea for the symbolism and metaphor behind it, then go into the studio and take pictures of myself, go into nature and photograph the landscape there, and by doing those two things initially I’m able to dive into that present moment of being mindful and understanding the experience that I’m having while photographing. As I move it into the digital world then I start to imagine all the possibilities these images possess. There’s a lot of experimentation, and I leave room for things to organically build upon each other. I am a digital photographer, I use digital cameras, mainly Photoshop, sometimes Lightroom a little bit to do some tweaks here and there. My process is pretty straightforward of building layers and layers of images and different digital techniques to manipulate the photographs.

JS: In your thesis you mention how stories of Black Americans usually start with slavery, and how you wanted to explore even further back to the start of creation. In what ways do science-fiction and the cosmos play into this idea?

GC: Well, I guess it’s re-imagined, you know, the history we’ve been given and told. So science-fiction, even though it’s, well, fiction, there’s still a lot of truth embedded in it. It uses reality to re-imagine the possibilities of a future. So that’s what I’m doing within my own work, looking at the history of African Americans and how we’re always told it’s born in slavery. Then here we are now. It’s digging further into the past and uncovering these different truths that allows me to envision a new possible future. It’s kind of speculative in nature because I don’t really have knowledge about my own ancestral history, so I’m diving into all these different cultures. Specifically in the work I look at Yoruba cosmology and understand their origin stories of our world and the universe, and understanding how that actually has a huge influence on the black population here in America because of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade coming from mainly the west coast of Africa. By looking at cosmology, the history, and these different themes it connects it specifically to the African diaspora, but I think one thing that’s also important is that it opens it up to a dialogue to talk about the humanity in all of us, because if we’re saying that we come from the stars then isn’t that the same for everyone? We have our cultural differences and traditions, and those should definitely be respected, but there’s also a lot of similarities between the cosmos and the way that people look at the sky to guide and direct their lives

JS: You deal with personal identity heavily in your projects, do you feel as though creating the images and text in this series helped you in exploring selfhood and your personal, individual representation?

GC: I do, I do. My whole process itself is very meditative, like I was saying before, this idea of mindfulness. So as I’m sitting and having a reflection on these really heavy thoughts and ideas, one about who I am as an individual, but how the world is going to look at me as well, and comparing the two I’d say it was definitely a healing process. This process reaffirms the fact that I am not limited by worldly visions of who I am because I’m a man or because I’m black, that we actually have freedom of expression and can expand and move beyond these labels and definitions. These are things that I already connected to in the past, but it reaffirms those thoughts and also opens my mind to the different ways that we can move forward in that direction so that we’re not bogged down, chained to these ideas and concepts of who we have to be because of what the world says. There’s actually freedom of choice in how we construct our identity looking at the essence of self.

JS: Finally, I wanted to discuss present times and how they may affect your future work. 2020 has been a hard year, both with the pandemic and fight for racial equality. Your work already deals with isolation and constructs of race, but do you think the way you look at these themes has changed through this forced quarantine and the greater attention put on injustices? How has your approach to making work changed during the pandemic?

GC: As I was finishing up my thesis all of this stuff was happening with COVID and the Black Lives Matter protests. It felt synchronous. I’m making this work about isolation and solitude and selfhood and concepts of race, and here the world is reflecting on that. I don’t think it’s actually changed the way that I’ve worked since the pandemic, but just strengthened in my mind the fact that I’m moving in a direction that is correct for me, and could act as a catalyst to bring a new awareness to these types of issues. The one thing in my mind when all this happened is just ‘what’s my role in it all?’ and that has been something I can really keep thinking and questioning because I’m not really an activist, I’m not really the type of person to be on the front lines. I’m more of a passive individual, and so thinking of that in terms of my role as a black artist in the context of society, it got me thinking a lot about that. I think I’m still diving into those questions and understanding what’s my place in it all, but what I keep inching towards is this idea of healing and art being this mechanism of healing. Hopefully by making this work it can bring about the humanity in others, it can show the intricacies and complexities, but also the way that we’re all intertwined with one another regardless of these constructs. I’m continuing in the way that I’m working, but thinking a little bit more about the reality of the situation and then how I can use the imagination and the ideas of an unreality to counteract it in a way to bring about a new perspective. Looking at these issues, it’s really heavy, it doesn’t leave a lot of room for positive thought, and I don’t want to continue into that sort of narrative. I do think it’s great to be aware of these things, but I guess I’m asking what’s the solution here?

Participating Artist

Granville Carroll is an educator and Afrofuturist photographer based in Rochester, NY. Carroll holds a BFA in photography from Arizona State University and an MFA from Rochester Institute of Technology, and his work explores the relationship between the external material world and the imaginative and vulnerable inner space of the mind.